When did standards become such a driving force in education?

Thinking back on my teaching career, I vividly remember being a new teacher and getting this giant binder that I could barely hold that had all of the K-5 GLCEs from Michigan and being told that these were the standards that I was responsible for. Throughout college, I had learned about different types of skills kids needed to know and different types of frameworks, but I don’t remember the push for standards in the same vivid way, and of course, we didn’t have the state tests that assessed skills by grade level either.

The first time I do remember standards being at the forefront of my work was during the special education part of my career when I had to create standards-based IEPs. I remember looking at what the standards said for math in first grade, then considering the child I was working with who was cognitively impaired or learning disabled, and trying to figure out how to expose the child to all those standards. That was my first real experience trying to interpret standards, trying to figure out what they meant and what to do about it.

Lofty Standards

Unfortunately, our standards in the United States are pretty overwhelming to most people. According to Marzano’s research, if we really want to cover all these standards that are set before us, we would need to change from a K-12 program to a K-22 program. Clearly, we’re trying to cram way too many standards into our students. And then, we wonder why kids are failing.

I feel that we have created many of our own at-risk students by asking them to be at a certain level when they’re just not prepared. In the United States, we have a set of fundamentals that students must learn at each grade level, but we don’t take into consideration that kids don’t all learn the same way or at the same speed. Not all kids come to school with the same academic behaviors, skills and background knowledge in place, and some students have a home life that is actually counter-productive to their academic success.

So, we have extensive and ambitious collection of standards laid before us, yet we have students coming in with all kinds of backgrounds and experience levels…how do we keep up with everything? How do you figure out what is essential for the kids to know and what will be most impactful for them?

As we’ve discussed in other blog posts, we have to take time to ask ourselves some questions as we prepare to teach our standards: What do we expect students to learn? How do we know when they’ve learned it? How do we respond when they didn’t learn it? How do we respond when they already have it?

I often look at other countries and wonder why we are not as successful as we could be in the area of math. A big part of it, I think, is because we’re asking children to know way too many standards. But a second component is that there are foundational skills that students must have in order to build knowledge at a higher level that students just aren’t mastering because the rigor level of our standards is much too high for some children to keep up with.

So I wonder – is less more? Can we look at our standards, as other countries do, and have three main essential standards in kindergarten that kids master, with the understanding that, if they master these three skills, they will continue to master more advanced concepts much more easily? Could there be essential skills identified in each grade level that would add new essential skills to the foundational part of the subject as students progress in subsequent grades?

Identifying the Target

Power standards (also called essential standards, priority standards, etc.) are a subset of the total grade level specific standards in each of the content areas that the students must know or be able to do by the end of the school year in order to be prepared for the next grade level. The key, however, is prioritization, not elimination. That doesn’t mean you don’t teach all the standards, but by giving priority to some standards, and really providing in-depth, targeted instruction in those areas, you can support students in a way that will help them be successful as they progress through their academic career.

Power standards (also called essential standards, priority standards, etc.) are a subset of the total grade level specific standards in each of the content areas that the students must know or be able to do by the end of the school year in order to be prepared for the next grade level. The key, however, is prioritization, not elimination. That doesn’t mean you don’t teach all the standards, but by giving priority to some standards, and really providing in-depth, targeted instruction in those areas, you can support students in a way that will help them be successful as they progress through their academic career.

Many of our schools are implementing power or essential standards as a way to combat the overwhelming body of standards for which teachers are responsible. So, how do we go about selecting those standards, and once they are implemented, how do we know whether or not students have truly mastered them?

What are the criteria for selecting power or essential standards? There are three main things we look at: endurance, leverage, and readiness.

- Endurance. We want the standards to have enduring value beyond just what they’re learning at the moment. I always ask: Will this skill or concept have value beyond this single assignment or assessment? Will the standard endure beyond this unit of study? Will the knowledge of the skill be important in future grades? We really want to find the standards that give us the biggest bang for our buck, so to speak, we want to make sure that kids have that essential piece in place before they move on.

- Leverage. Can the standard be applied, not only in that content area, but also other places? If kids could understand this concept, it would be appear in different subjects as well. Of course there are lots of things that go together in science and math, but leverage should really be able to be applied in more than one area. Does the standard have a multi-disciplinary connection? Are the standards relevant to other things that we’re learning? We definitely want power standards to be able to be connected to what we’re learning in all areas.

- Readiness. When the standard represents an essential skills for success, within that unit of study, does it contain the readiness that the kids need to move on? Does the standard contain precursor content skills that are necessary for that next grade level or unit of study? We want kids at an early age to be able to understand and apply some of the different properties of addition and subtraction, like the commutative property or the associative property and the relationship between, so that when they start to learn algebraic equations, they’ll have the readiness they need to apply those concepts in a new arena.

When picking power standards, we want to avoid the misconception that those are the only standards that are taught. The goal is for students to leave that grade level without gaps in their learning. We don’t want to just cover the mile-wide list of topics at an inch deep, we want to be sure that we aren’t eliminating standards at the expense of going a mile deep. Additionally, we’re not trying to lower the rigor of the curriculum by selecting power standards. We don’t want to dumb down any of the content, but rather prioritize it to help students achieve the readiness they needs.

The process of identifying power standards is unique to each grade level, school and district. You can’t just go google “priority standards” or “power standards” and find a list of things you need to work on for the year. Teachers must be heavily involved in the process since the identification of power standards is a key step to help a district work towards a common language and it will require each teacher to teach certain concepts in the same way.

Organizing the Standards

This is one of the exciting things we’ll be doing with some of our project schools this spring! We’ll be working with districts on an analysis of their data in order to determine what their priority standards are and where they are within the process of mastery of those standards.

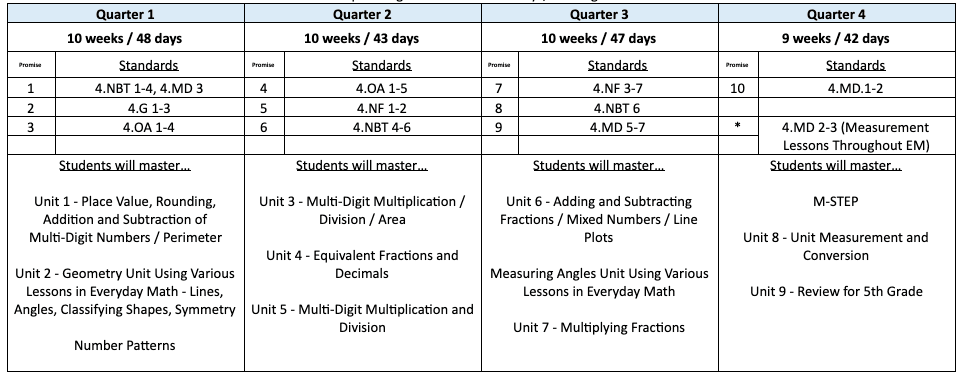

One particular school organizes their standards into something they call quarterly promises. They’ve taken their standards and, based on the number of instructional days they have for each grade level, they have prioritized standards that have a heavier weight and those that may only need a light touch. Then, as a teacher, I can look at the standards for that quarter and make a strong decision about what to teach based on the pacing of our math book and making sure students understand the power standards to mastery. This also works if you’re on trimesters – just divide by three instead of four!

Here’s an example of quarterly promises for 4th grade in one of our Michigan districts:

Click here to view the template in Google Docs. To create your own, editable, copy, of the template, click the Use Template button in the top right.

I believe that every teacher starts their day with honorable intentions to teach their students to the best of their ability. They are not just sitting around in classrooms, not teaching standards or not teaching the correct standards. However, they get overwhelmed in the course of the day and end up just trying to “make it through” the math lesson. This framework of power standards, which creates this common language in school districts, will really help teachers to know where they’re going and be able to teach more effectively.

A few weeks ago, in her guest blog, Kathleen talked about the idea of backwards design. It’s so important to really understand what the expectation is, where our priority is within the district, what needs we need to meet with our kids. But not every teacher has the skills or the time necessary to plan this way across the scope of six grade levels within an elementary building!

The Next Step

The school that has been operating on these quarterly promises has definitely seen an increase in their test scores state-wide, which is great! However, I met with them just the other day and their question was, “What can we do to increase these scores, not just stay the same?”

They had color-coded student mastery of the standards by red, yellow, and green, and we were looking at a 4th grade standard. Two students had mastered it to a green level and one had it at a yellow in two different classrooms. I asked about the assessment that was given and about the level of complexity of the questions being asked to determine mastery at these different levels. The principal didn’t really know what assessment teachers were using to gauge whether or not the students had mastered the power standard.

Common assessment is the next step. Once you’ve mapped out those essential standards and put them on a quarterly promise sheet so teachers have a visual understanding of where the focus is in a district, we must have a common way to assess them as well. If not, are we really comparing apples to apples, or are we comparing apples to oranges?

Next week, we’ll explore the idea of common assessments based on the depth of knowledge. Stay tuned!